The Concept of Abdication (abdicatio) From Ancient Rome to the Papacy

Abdication (from Latin abdicatio and Greek apokiryxis) historically referred to the act of a father removing his son from the family home, renouncing his paternal guardianship. While this institution had legal effects in ancient Greece, in Rome, these consequences only occurred if the abdication was accompanied by disinheritance or emancipation.

Over time, the term came to signify the voluntary renunciation of an office or status but only in reference to public office.

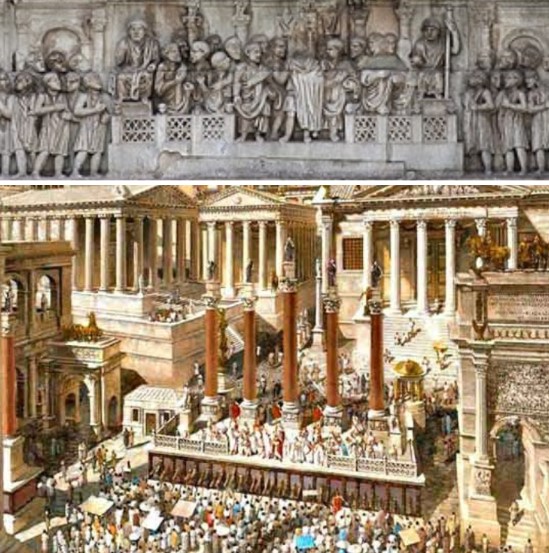

Left part of a plaque from the Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus known as the “Census frieze”. Marble, Roman artwork of the late 2nd century BC. From the Campus Martius, Rome.

Abdication in Roman Legal Terminology

In the Roman legal framework, abdicatio referred to the voluntary renunciation of something, whether it be a position, right, or inheritance. For example, a person could renounce an inheritance, sell themselves into slavery, or leave their gens (a Roman familial clan). In all these cases, the term abdicatio applied to the voluntary surrender of status or rights.

This concept extended to various aspects of personal life and family law. In cases of guardianship, there was even the possibility—although it remains a topic of debate among historians—of renouncing patria potestas, the legal authority a father held over his children and descendants.

Public Significance of Abdication in the Roman Republic

While abdicatio had relevance in private matters, its most prominent use and importance arose within public and political contexts, especially during the Roman Republic. In this era, abdication signified the voluntary resignation of a magistrate from their office, a principle that highlighted the limitations on the duration of public positions. Roman magistrates, particularly those in the highest offices, could not be forcibly removed from their positions or stripped of their powers by any external entity. Instead, they were expected to renounce their position themselves. This system was rooted in the oath magistrates took to uphold the laws, and it was only by their personal decision that they could step down from office.

A notable example is the case of the censores (censors), whose office was established in 443 BCE and functioned until approximately 350 CE. The role of the censor, which evolved from conducting censuses to overseeing public morality, state finances, and construction, was one of the most prestigious positions in Rome. For instance, the censor Appius Claudius famously exceeded his legal term, continuing to exercise his powers even after his term had expired, as there was no external force that could compel him to relinquish his authority.

When it came time for a magistrate to relinquish their office, the resignation was a formal and solemn occasion. The magistrate would present themselves before the people, often at the rostra (the public speaking platform in the Roman Forum), and publicly announce their abdication. They would offer a report on their term in office, swear that they had observed the laws, and formally relinquish their powers. This ceremony became known in common parlance as abire magistratu or eiurare magistratum.

Arch of Constantine, Oratio set in the Roman Forum: the five columns behind the imperial stage are the monuments on the Rostrums

For some offices, such as the dictatorship (which lasted six months) and the censorship (eighteen months), it was common for officials to resign before the end of their term. The magister equitum (cavalry commander), a subordinate to the dictator, was expected to resign upon the dictator's orders. In all cases, though, it was understood that abdication was voluntary, even if pressures from the Senate or other political bodies played a role in encouraging the resignation of inept or controversial magistrates.

Abdication in the Roman Empire

As Rome transitioned from a republic to an empire, the meaning of abdication began to change. The word abdicatio eventually became reserved solely for the voluntary resignation from office before the appointed time. Such resignation was naturally not permitted in the military imperium unless a successor had already been arranged. This early abdication could happen for various reasons. Sometimes the Senate acted to encourage incompetent magistrates to step down, but formally the resignation had to always appear voluntary.

During the Empire, magistrates were mostly appointed by the Senate following a commendatio (recommendation) from the emperor, and later increasingly appointed directly by the emperor. The emperor's imperium maius (greater authority) allowed him to order the cessation of a magistrate's powers without the need for voluntary abdication. In the later stages of the Empire, there was a unique example of an emperor's abdication: that of Diocletian, who not only abdicated but also forced his colleague Maximian to do the same. This event seemed peculiar and nearly incomprehensible to their contemporaries, and modern scholars have sought to explain it with various theories.

Diocletian and Maximian. Gold medallion (equivalent to 10 aurei). AD 293/294.

Abdication in the Papacy

The concept of abdication also found its way into ecclesiastical practices, most notably within the Roman Catholic Church. Even the Pope, the highest religious authority in Christianity, can abdicate. Throughout history, several notable papal abdications have occurred. One of the earliest examples is Pope Celestine V in 1294, whose resignation was driven by his desire for a more ascetic life. His abdication sparked a heated debate among canon lawyers over whether a pope could indeed abdicate and whether such a resignation required the approval of the College of Cardinals or other church authorities. Celestine V settled the issue by declaring that the pope could freely resign without needing consent from anyone else, a principle later affirmed by Pope Boniface VIII.

More recent examples include Pope Gregory XII in 1406, who abdicated in an attempt to end the Western Schism, and Pope Benedict XVI in 2013. Benedict XVI’s resignation was notable for being the first in almost 600 years, and it sparked widespread attention and curiosity. He announced his decision in February 2013, citing his advanced age and declining health as the reasons for his abdication. Upon his resignation, Benedict assumed the title of "Pope Emeritus," and a conclave was called to elect his successor, Pope Francis.

Pope Benedict XVI stands by the salvaged remains of Pope Celestine V, in the 13th-century Santa Maria di Collemaggio Basilica, in L'Aquila, Italy, in 2009.

Papal abdication carries significant implications. Upon resignation, a pope loses all rights, privileges, and jurisdictional powers associated with the papacy. Importantly, the abdication does not require the approval of the Cardinals, bishops, or any other body, ensuring that it remains a personal decision.

Last update: October 24, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE