Herodotus

The Father of History and His Journey from Myth to Historical Inquiry

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (circa 490–424 BCE) is widely regarded as the "Father of History." His works not only set the foundation for historical writing in the Western world but also offered a comprehensive narrative of the Greco-Persian Wars, combining detailed historical accounts with rich storytelling. Herodotus's life was marked by travel, intellectual curiosity, and a dedication to understanding the cultural and historical contexts of various civilizations. His writings, especially his masterpiece known as "The Histories," reflect both his fascination with the world around him and his ambition to document human achievements, myths, and conflicts.

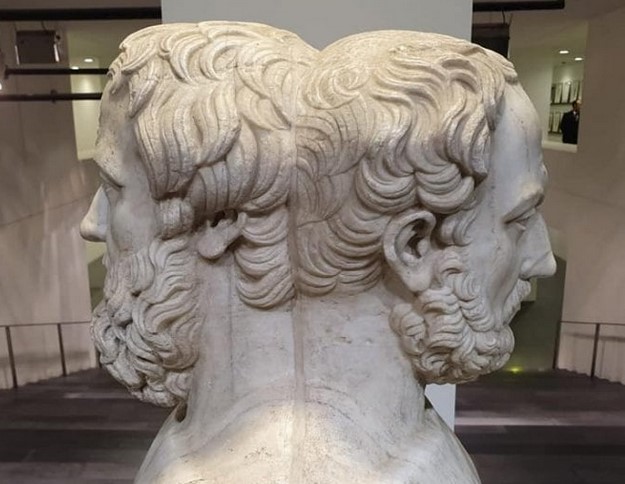

The double herma of Herodotus/Thucydides preserved at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples

Born in Halicarnassus (modern-day Bodrum, Turkey), Herodotus grew up in an era marked by political turbulence and cultural exchanges. He was exiled to Samos for a time but returned to Halicarnassus after the fall of its tyrannical rulers. Later, he moved to Athens, where he interacted with prominent figures like Pericles and playwright Sophocles, forming friendships that would influence his perspective on Greek society and politics.

Herodotus's wanderlust led him to travel extensively, journeying through Asia Minor, Egypt, Persia, North Africa, and even parts of Europe. His voyages were more than mere exploration; they were opportunities to gather information, observe local customs, and collect stories from the people he encountered. While there is debate over whether Herodotus personally visited every region he described, it is likely that he supplemented his observations with data from written sources and oral traditions.

The Histories: Structure and Content

Herodotus's magnum opus, The Histories, is a monumental work that was later divided into nine books by Alexandrian scholars, each named after one of the nine Muses. This division, although made after Herodotus's time, organizes the narrative into a coherent framework that blends historical fact, cultural analysis, and storytelling.

Book 1 focuses on the history of Lydia and Persia up to the death of Cyrus the Great.

Book 2 is dedicated to the history of Egypt and its conquest by Cambyses, Cyrus's successor.

Book 3 details the reign of Cambyses and introduces Darius, covering his rise to power and his subsequent campaigns.

Book 4 shifts its focus to Scythia and Libya, interspersed with digressions on the customs of these regions.

Book 5 recounts the Ionian Revolt and dives into the history of Sparta and Athens.

Book 6 describes the subjugation of Ionia and the famous Battle of Marathon between Greeks and Persians.

Book 7 is centered on Xerxes's invasion of Greece, leading up to the heroic stand at Thermopylae.

Book 8 narrates the naval battles of Artemisium and Salamis, key moments in the Greco-Persian Wars.

Book 9 concludes with the Greek victories at the battles of Plataea and Mycale, signaling the end of Persian expansion into Greece.

Herodotus's Historical Method and Themes

Herodotus’s work is notable for its methodology, blending mythology, cultural anecdotes, and empirical observations. Unlike purely factual chronicles, his approach involved crafting a narrative that interwove factual history with cultural and philosophical reflections. This technique, while criticized by some for its lack of rigorous analysis, is also what gives "The Histories" its unique charm and insight into the ancient world's mindset.

He often provided multiple versions of events, leaving readers to decide which seemed most credible, rather than imposing a single authoritative interpretation. His reliance on oral traditions and eyewitness accounts underscores the importance he placed on diverse sources, although it occasionally led to criticisms of his work as being overly reliant on hearsay.

Criticism and Reception

In ancient times, Herodotus faced criticism from both his contemporaries and later historians. His detractors accused him of being a philobarbaros (a lover of non-Greeks) because of his fair and sometimes admiring descriptions of Persian and Egyptian cultures. This was in contrast to the prevailing view among Greeks, who often considered their own culture superior to that of the so-called "barbarians." Herodotus did not blindly accept Greek superiority, which led to accusations of being too sympathetic toward foreign customs and traditions.

However, despite this criticism, his work also contained a clear admiration for Athenian democracy and Athenian achievements, particularly in the Greco-Persian Wars. He often portrayed Athens and its leaders as the true liberators of Greece, in contrast to the Thebans and Corinthians, whom he depicted less favorably due to their opposition to Athenian ideals. His attitude towards the Spartans was more balanced; while he acknowledged their bravery, he subtly criticized them in comparison to the Athenians.

Religious Beliefs and Views on Fate

Herodotus's religious outlook was complex and sometimes contradictory. He exhibited a blend of rational skepticism and deep-seated belief in the divine. While he occasionally rationalized myths, reducing them to mere stories or allegories, he also accepted oracles, prophecies, and divine interventions as genuine influences on human affairs. A recurring theme in his work is the concept of divine envy (phthonos theon), the idea that the gods intervene to humble those mortals who become too proud or successful. This notion reflects the belief that human hubris invites divine retribution, a key element in Greek thought.

Herodotus's Style and Artistic Merit

Herodotus's writing style is celebrated for its simplicity and narrative flow, making his accounts both engaging and accessible. He employed the Ionic dialect, which was well-suited to storytelling, with a preference for parataxis (the use of clauses or phrases placed side by side without subordination) rather than complex syntactic structures. This approach lent his narratives a directness and clarity that helped to convey the drama and significance of historical events.

His ability to blend historical fact with anecdotal stories, observations on customs, and insightful commentary created a narrative rhythm that remains captivating to readers even today. The charm of his storytelling lies in his skillful weaving of human interest with the grand sweep of historical events, making his work both an informative record and a literary achievement.

The Legacy of Herodotus

Herodotus's legacy as the first true historian endures in his lasting impact on historical writing and his influence on subsequent generations of scholars. His portrayal of the Greco-Persian Wars set a standard for historical narrative, blending rigorous inquiry with engaging storytelling. The statue-bases and portrait copies of Herodotus, discovered in sites like Halicarnassus and Pergamon, alongside his image on coins and statues, indicate the esteem in which he was held even after his death.

His approach has inspired countless historians to adopt a narrative style that seeks to understand the broader cultural and human elements of historical events, rather than simply listing dates and facts. Although Thucydides later adopted a more analytical and critical method, Herodotus's emphasis on the human experience within the tapestry of history remains a foundational element of historical studies.

Last update: October 18, 2024

Go to definitions: A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z

DONATE

DONATE

See also: